Ethiopia’s geology shows extraordinary potential for exploration and development. This page provides information, maps and data on just some of the opportunities for investing in the following commodities:

- Metallic minerals (gold, platinum, iron, nickel, chromite and base metals)

- Fertilizer raw minerals (potash and phosphate)

- Gemstones (sapphires, emeralds, fiery opals)

- Energy minerals (lithium, graphite and tantalum, oil shale and coal)

- Cement raw minerals (limestone, gypsum, clay, pumice)

- Ceramics raw minerals (kaolin, feldspar)

- Glass raw minerals (silica sand)

- Dimension stones (marble, granite, limestone, sandstone, diatomite, bentonite, soda ash, salt, graphite and sulphur)

- Natural gases and hydro-carbons

Gold

Ethiopia’s gold deposits are clustered in a Proterozoic basement, which covers about 18% of the country. A considerable part of this area has already been surveyed by aerial geophysical surveys and geochemical mapping.

Good news for investors is that significant gold mineralization has been found in three regions:

The Western greenstone belts

The presence of gold mineralization in these areas has been known since the early 1930s, and several of the belts host gold. The most promising gold occurrences are located in the Tulu-Kapi and Ankore areas.

The Northern greenstone belts

The most promising discovery in this greenstone belt is the Terakimiti prospect where trenching and drilling has revealed grades of up to 16 grams a tonne. The deposit contains an estimated total of 20 million tonnes of ore with a grade of 0.29 grammes per tonne and there is also 6 million tonnes of ore that contain 2.24% copper.

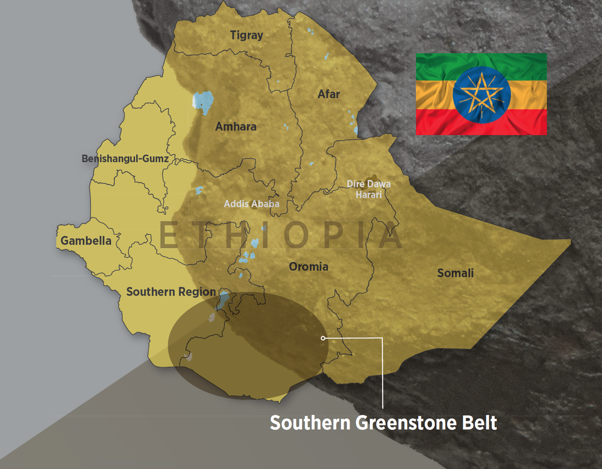

The Southern greenstone belts

There are already two gold mines in the Southern greenstone belt. The Lega Dembi mine in the Oromia Region has two active sites already in production – one open pit and an underground gold mine. The Sakaro mine is an underground mine in the Gujji zone in Oromia Region which is still under development.

There are additional opportunities for investors in epithermal gold. The East African Rift Valley transecting Ethiopia hosts a large number of geothermal fields which are used for power generation, and a low-grade epithermal gold deposit was discovered at Tendaho in the Afar region. Geothermal drilling revealed highly silicified zones returning gold grades of 1 gram per tonne. Currently, investors are intensively exploring to better define the pockets of epithermal gold around the northern part of the country.

Potash

Of all of Ethiopia’s mineral potential, potash has garnered some of the greatest interest.95% of the world’s potash is mined for use in fertilizers, while the rest is used for feed supplements and industrial production.

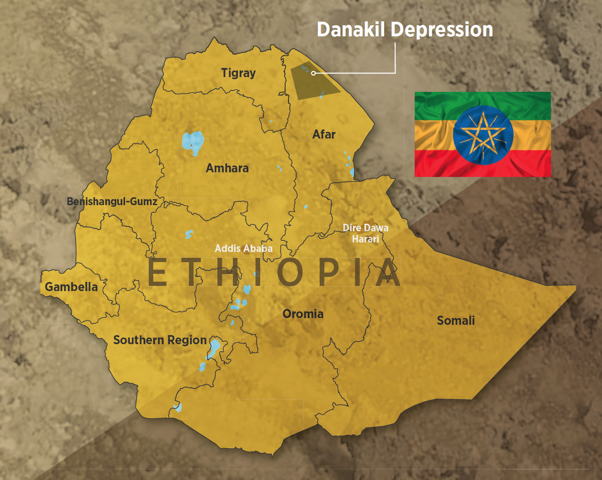

As can be seen in the map below, potash deposits can be found scattered around Ethiopia’s northern, central and southern regions. However one area is particularly exciting: the Danakil Depression in the far north of the country.

The Danakil Depression is calling out for exploration. Danakil lies at the junction of three tectonic plates, and was formed as a result of the African and Asian continents moving apart. This caused rifting and volcanic activity, resulting in its complex and alluring geology.

The salt formations on the surface cover an area of about 450 square miles, but only a small part of this area has been explored. One can see on Mount Dallol colourful layers of salt about 20 or 30 centimetres thick, with thin clay and gypsum layers in between, lying exposed to the air.

Not only is the Danakil Depression the hottest place on Earth in terms of year-round average temperatures, but it is also one of the lowest– sitting 100 metres below current sea level. Past exploration undertaken by various companies has confirmed the presence of two ore bodies at Dallol:

Significant reserves of natural resources for the production of Sulphur of Potash (SOP) having been identified during companies’ feasibility studies in recent years.

Phosphate

There is a very high demand for phosphate in Ethiopia, due to its importance as a fertilizer. Phosphates are amongst the most important nutrients agricultural products need: moreover, it is a nutrient that is naturally scarce in Ethiopia’s high lying areas. This is a concern as agricultural still plays an indispensable role in Ethiopia’s economy, contributing roughly 34% to Ethiopia’s GDP.

Importing fertilizers, furthermore, is prohibitively expensive. As a result, there has been extensive exploration for phosphate in recent times. These efforts have uncovered to At least two major mafic complexes, Bikilal in the west and Melka Arba in southern Ethiopia. However more work is required before we can tell whether extracting these resources would be economically feasible.

Sapphires

The gemstone world was rocked in November 2016 with the news that high quality deposits of new and unique sapphire had been found in Tigray. Early samples taken near the villages of Awaet, Adi-Shumbro and Chila confirm the sapphires are of an impressive quality, good size and with a wide variety – easily comparable to the sapphires of Madagascar. These deposits fall within the western greenstone belts that run from the northeast to the south-west of Tigray, which is primarily an agricultural and cattle farming region. These sapphires are dominated by a blue-yellow-green series but they also include exciting varieties such as red, purple, white, orange, yellow and even a deep pink. All indications are that Ethiopia’s newly discovered deposits are ripe for commercial exploitation. Limited geological and geochemical work in the belt to define the mode of occurrence means that the field is wide open for investors to bring these extraordinary gemstones to a global market.

Ethiopians have been mining sapphires artisanally for many years in Tigray, the northern-most of the nine regions of Ethiopia, particularly around a local town called Chila. There are three well-known types of sapphire in Ethiopia. Blue Star sapphire and Fancy sapphire are common, but it is the ‘colour-changing’ sapphire from the areas surrounding Chila which is of highest quality and commercially sought. These colour changing gemstones feature a blue, star and green series and can be classified as either ‘High-Fe’ sapphire or ‘Low-Fe’ sapphire, and are formed by magmatic and metamorphic processes. Ethiopia also produces the rare and coveted pink sapphires known as ‘padparadscha’ (from the Sinhalese word meaning aquatic lotus blossom), which has seen renewed interest since England’s Princess Eugenie revealed her salmon padparadscha engagement ring in early 2018.

Emeralds

International gem forums were buzzing in 2017 with the news of the high quality and size of Ethiopia’s very recently identified emerald deposits. Discovered in August of 2016 by artisanal miners looking for tantalum, these new finds are comparable to those mined in Colombia in terms of hue and quality.

The emerald deposits are located in the Sebo Boru district in the beautiful coffee-producing Oromia Region in southern Ethiopia, where the rural villages of Kenticha and Dermi host particularly high-quality deposits. Commercial emeralds are suddenly a real and urgent opportunity for investors – Ethiopia is calling. Ethiopia is currently exploring ways to establish a traceability and identification protocol for emeralds, in order to certify their origin and maximise their value.

Most emeralds are then exported to Switzerland, Australia and the United States. In 2017, Ethiopia exported 2,290kg of emeralds, surpassing the export of opal and sapphire which are the current major gemstone types exported.

Opals

Ethiopia is well on course to become the first challenger to Australian opals. In 2008, the discovery of spectacular Wollo opals in northern Ethiopia changed the game.

This high quality, structurally stable and strikingly beautiful opal was exhibited at the Tucson Gem and Mineral Show in 2010, and Ethiopian opals have been unstoppable ever since.

Between 2000 and 2014 alone, Ethiopia’s exports of opals increased by 136.6%. More discoveries followed – there are now four types of opals being mined in Ethiopia, with the majority only discovered in the last decade.

Four types of Opals

Tantalum

Ethiopia is already the sixth biggest producer of tantalum in the world with the potential to dramatically increase their standing.

Adola in southern Ethiopia is the most exciting region for tantalum. It is known to host a long and linear belt of this rare metal occurrence of tantalum and niobium in its Kenticha Belt, which extends for over 100 kilometres and covers an area of more than 250 kilometres.

Three types of ore have been identified in the deposit:

- Primary ore: rare tantalite bearing granite-pegmatite with complex Ta-Nb-Li-Be mineralization has meant this is a world class ore reserve

- Lateritic-type ore: a ‘rind’ developed over the pegmatite and granite as a result of intense weathering

- Elluvial, delluvial and alluvial placer ore: marked with high quality Ta-Nb

Together, the weathered ore over the primary ore of pegmatite in the Kenticha belt have been recognized as one of the best deposits of this type anywhere in the world.

There is currently an opportunity to develop the Kenticha Mine — which, given the quality of the resource, is one of the best opportunities on the market.

The Kenticha mine appears to be located on one of the world’s largest tantalum resources. It is estimated to have a probable reserve of 17,000 tonnes and to have the potential to produce as much as 9,000 tons of processed tantalum products over the next 15 years

Located approximately 550km south of Addis Ababa at Adola, the 25 year old mine is the property of the state-owned Ethiopian Minerals, Petroleum and Bio Fuel Corporation (EMPBFC), which is looking for partners to help develop the asset.

Graphite

In southern Ethiopia, right on the Kenyan border, and on the southern edge of the Southern Greenstone Belt, sits the Moyale deposit with an estimated reserve of 460,000 tons of well-crystalised and flaky graphite.

Most likely of sedimentary origin, the graphite in the Moyale area is hosted by quartz feldspar-mica schist and quartzite which form continuous bodies extending for hundreds of meters. Studies have shown Moyale’s graphite content to be moderate, but generally fine-grained.

The gold and base metal bearing belts in the Adola region in eastern Ethiopia, and others in the west and the north of the country are also all known to contain graphite. Several long belts of graphitic schist extend for many kilometers through the Adola region, specifically in the Bekeka, Kenticha, Kibre, Mengist-Chembi and Chembi areas. The MoMP, together with a university-industry linkage, is currently undertaking a study to better qualify parts of these graphite resources.

Lithium

Are you looking to explore for lithium? Ethiopia is full of potential. Both the salt brines in the marine strata of southern Ethiopia and the saline springs associated with volcanic activity in the Ethiopian rift of Afar are likely to contain lithium, in addition to the trace elements and edible salt currently produced.

Private sector investors could bring the requisite technology and expertise to Ethiopia, which are urgently needed to better analyse the country’s lithium potential.

Petroleum

This website has a dedicated section mapping Ethiopia’s available petroleum blocks, including detailed information on the surrounding geology and information on the oil fields. We invite you to click the button below to learn more about petroleum.

Oil Shale

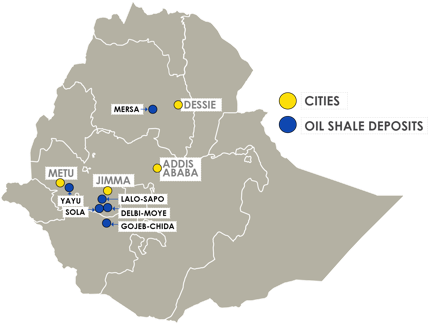

Oil shale has also been discovered scattered around Ethiopia’s south western regions. What has been found so far exhibits tremendous potential both in terms of quality and quantity. The reserve is estimated at ~1 billion tonnes. In addition, the shale has a fantastic total organic carbon (TOC) of up to 55- 60%, and has been in the following thick shale formations:

- Urandab Shale – ~ 400 m thick

- Bokh Shale – up to 800 m thick

- Shale formation – within Carbonate rocks

Miocene-Oligocene deposits –which are important source rocks – can be found in the west/ southwest of Ethiopia. Recent mapping results found outcrops also in the northeast/central part of Ethiopia.

Coal deposits

Studies related to exploration and estimation of coal resources in Ethiopia are at an early stage and are still ongoing. However the Geological Survey of Ethiopia has made some notable progress in its coal-related investigations, and has delineated several coal deposits, most notably in the Geba Basin, the Deleb-Moye Basin and Mush Valley Basin. The coal reserve is around 600 Million tonnes by present estimates with 70% of this coming from the Geba Basin. These areas are illustrated on the map below.

The Deleb-Moye Basin is another area that is worth a look for investors interested in coal. The coal found here is of good quality and can be used for thermal combustion, there is considerable land area available, and there is potential for open-pit coal mining, making coal seam development here particularly commercially viable.

Bentonite

Bentonitic clay can be found primarily in the northern parts of Ethiopia, in the Afar region, as shown on the accompanying map. Afar’s total reserve is estimated to be over 135 million tonnes with an average swelling capacity of 6.1.

The most interesting Bentonite sites are a series of sites clustered around Hadar, as indicated on the map. They are Ledi, Gewane, Hadar, and Warseiso Hadar. Significant occurrences have also been found on Lake Abaya’s Gidicho Island in the Rift Valley in the centre of the country.

Tests conducted so far confirm multiple possible applications for Ethiopia’s Bentonite. The Bentonite from some beds could be used for the preparation of drilling mud and iron ore palletization, and could potentially have a foundry application as well.

Samples from Warseiso and Ledi (near Hadar – see map), confirmed that the bentonite there could also be used in waste water treatments.

Diatomite

Diatomite is a powdery mineral composed of the fossilised remains of microscopic single-celled aquatic plants called diatoms. It has a range of possible applications, including dimension stone.

Ethiopia’s overall diatomite reserves are estimated to be 1.57 million tonnes. Of that reserve, and crucially for investors, 310 000 tonnes are of high quality.

Exploration work has identified more than 12 diatomite deposits and occurrences in the Ethiopian Rift Valley area. The best diatomite deposits are found in the central part of the Rift, in Ethiopia’s Lakes Region, near the centre of the country as indicated on the above map.

The ore found in all four in this area (specifically in Chefe Jilla, Adami Tulu and Gada Motta) show promisingly high grades, with:

- SiO ranging from 84.5 to 86.5%,

- Al.O. from 3.1 to 3.7%,

- Fe.O. from 1.5 to 2.4%, and

- CaO from 0.1 to 1.9%.

Gypsum

Gypsum is a versatile mineral with many applications. It plays an important role in controlling the rate at which cement hardens, as one example.

As this map shows, Gypsum can be found primarily in three areas in Ethiopia: in the Abay Basin, the Mekele Outlier and the Ogaden Basin – with the first two looking particularly promising. There are exciting opportunities for exploration at these two sites, both of which have extensive deposits, and where some pre-existing exploration has already taken place, meaning that knowledge can be further built upon.

- The Mekele Outlier covers an area of 17,400 square kilometres area and is primarily made up of gypsum, shale, marl and claystone. This sequence, which is 60 to 250 meters thick, contains thin beds of gypsum and dolomite and a few beds of yellow coquina. Made up of gypsum beds and lenses laminated shale, marl, and limestone. The gypsum bed reaches is two meters thick in places, confined within a thick shale unit of various colours.

- Al.O. from 3.1 to 3.7%,